“To the Wonder” almost settles for love

“To the Wonder” is so close to being a goddamned masterpiece. Terrence Malick, the writer and director, is a big name in “film circles,” in dusty basements and over-clean libraries, but he’s always been too “out there” to swim in the mainstream, too much of a winding, swirling, often muddy rivulet.

He’s a spiritual existentialist who taught philosophy at MIT before he moved into film.

He made two movies in the Seventies, “Badlands” in ’73 with Martin Sheen and Sissy Spacek, and “Days of Heaven” in ’78 with Richard Gere. Then he didn’t make another movie ‘til “The Thin Red Line” in ’98. He made “The New World” in 2006, with Christian Bale and Colin Farrell, then “The Tree of Life” in 2011, with Brad Pitt. Now he’s made “To the Wonder,” with Ben Affleck and Olga Kurylenko, and he has two other films coming out within the next year. Mr. Reclusive I’ll Get Back to You in Two Decades is on a roll.

How to recognize a Malick film: saccharine, philosophizing, spiritually searching voice-overs; close-ups of characters moodily staring into the camera or toward the horizon; stunning wide angles showing characters against the horizon at dawn or sunset, usually with either swaying fields or pumping industrial machinery. There’s a lot of dialogue about people connecting with each other, or with nature – Malick’s all about nature. He looks at humankind like he was an extraterrestrial making a documentary for the Discovery Channel, like we’re just another animal species.

But he also veers off into that ponderous “objectivity” that defines the work of Stanley Kubrick, Christopher Nolan, David Fincher, the Computer Filmmakers. “The Tree of Life” and “To the Wonder” have a deeper feeling for humankind than Malick’s previous movies, which is why they’re probably his best.

His films are so abstract that the plot almost disappears under the images and feelings, not that they’re exactly emotional rollercoasters. My dear Pauline Kael described “Days of Heaven,” his best-liked film, as “an empty Christmas tree: you can hang all your dumb metaphors on it.” Well, that’s Malick. His selling point is that his Christmas trees are f—— pretty.

“To the Wonder” is probably his best Christmas tree, although, damn it, I’m sorry, I’ve got to admit I haven’t seen “Badlands” or “The Thin Red Line.” But “To the Wonder” is one of only two Malick movies I’ve seen in which he, mostly, almost, fulfills his conceit, the other being “Tree of Life.” His films just seem more personal now. It doesn’t seem like he’s throwing out a neurotic net of existential worries and ideas and draping it over a plot: now it seems like he actually knows something.

If I were to read this, and I didn’t know Malick from Spielberg, I’d think, “Why bother with this guy? Why not ditch him and go for Brian De Palma, or Wes Anderson, or Luc Besson, or anyone else with a rabid heartbeat and red blood?”

The images, that’s why: the stuff that makes film more than illustrated novels and novels more than blueprints for films – if words and film could do each other’s jobs we wouldn’t have “To the Wonder.”

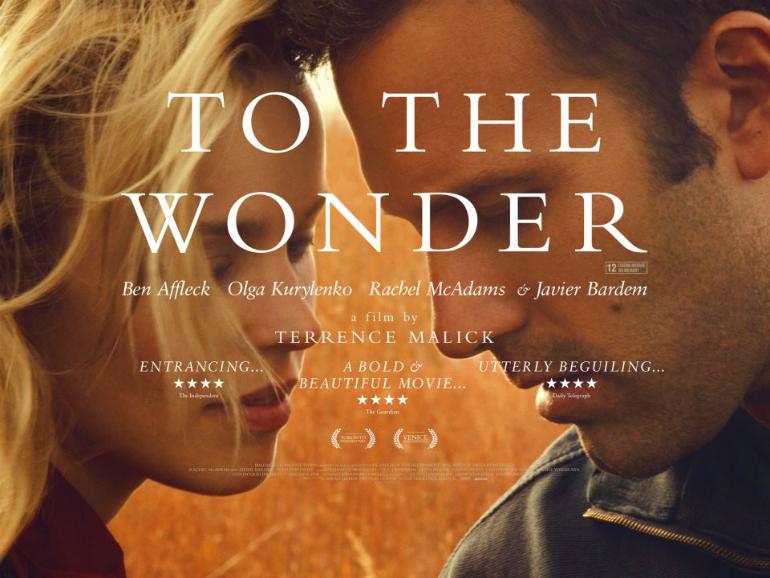

“To the Wonder” has the most beautiful images Terrence Malick has ever filmed. Malick’s images have always been some of the prettiest in recent movies – but “pretty” ain’t “beautiful,” and “To the Wonder” is frigging beautiful. It’s a love story, see, a breezy small-town existentialist drama: you got Ben Affleck, who meets Olga Kurylenko, playing a French lady, in Paris, where he convinces her and her daughter to move back to the States with him. But once they’re there, everything changes. Where’d the love go?

Also starring Javier Bardem as a hyper-serious, lost priest, trying to figure out God and what He has to do with him, and Rachel McAdams as an absolutely charming rancher who briefly grabs Affleck’s attention.

The most thrilling moment: upon learning that Kurylenko has been involved with another lover, Affleck, who post-“The Town” remains a hulking, stooping beast of a man, pulls over his SUV, stomps around the vehicle, and smashes the rearview mirror right off the side of the car. Scary stuff in reality, but in Malick’s subdued existential pool of a film, a moment of intense emotion like this, especially from Beast Affleck, is like listening to concertos for three hours and then seeing the New York Dolls.

Anyway, it isn’t a straight romance in the down-to-earth sense. It’s an intellectual-spiritual search, surprisingly like Jean-Luc Godard’s movies (but more “Film Socialism” than “Breathless”). The characters in “To the Wonder” see love everywhere, even in the clouds, but wonder where it comes from and where it goes, what’s real and what isn’t. It’s a search for God: Malick seems to see love as an earthly manifestation of the Big Guy in the Sky. But he must be more in touch with that Guy, or with that love, than he’s ever been before: this is by far the most beautiful dialogue he’s ever written – hell, this is some of the loveliest verbal language in recent movies.

The movie starts with this poetic narration from Kurylenko: “Newborn. I open my eyes. I melt. Into the eternal night. A spark. You got me out of the darkness. You gathered me up from earth. You’ve brought me back to life.”

Mr. Malick! Thou hath become the Byron behind the projector! That’s not even the most beautiful line – and imagine those kinds of words put against a breezy midwestern sunset as a jet flies overhead and Olga Kurylenko dances and sways to inaudible, natural music – a handheld shot.

Pardon moi if I seem dismissive: I don’t like the “cerebral” filmmakers. They seem dehumanizing and cynical, even nihilistic.

Malick’s cerebral side, which usually ends up ruling his films, is so desperately serious it’s almost comic at times, and the only thing preventing “To the Wonder” from being a masterpiece is its final third, in which it falls back into Malick’s sea of unorganized ideas and worries and basically amounts to an intellectual fart.

But his spirit is showing. Finally Malick’s movies are driven by his heart as much, and more, than his head. It’s like he’s been looking over the Cinema Car’s control panel, the stickshift, the windshield wipers. Now he’s hit the gas, and he’s starting to move forward, and he’s looking out the window – not wondering about “Days of Heaven,” but driving us “To the Wonder” with him, an often lovely place.

Tom Benton joined the Basement Medicine staff in spring 2011, assuming the position of editor-in-chief in spring 2012. He continues in that capacity...