The MFA Thesis show “Retratos de Espaldas,” or “Portraits from the Back,” is currently showing in the Julian Scott Memorial Gallery. The show is dominated by life- and larger-than-life size paintings of full-body portraits, all depicting people in the crowds of “el mercado,” or the market. The paintings document a physical and philosophical journey for the artist’s identity.

Chepe’s artistic search for identity is reflected in a story about his own name. “In Nicaragua, if I introduced myself as Chepe, you’d just know my name was Jose,” he said. “Same thing if someone came up to me and told me his name was Paco—I’d know his name was Francisco. But here, it’s too confusing, everyone thought it was two different names. So the art teachers gave up and said, ‘Alright, your new name is Jose Chepe.’ And I liked it.”

This tale parallels a lot of Chepe’s experience in his life as an artist. While he was born in California, he feels that his roots lie in the city of Granada in Nicaragua, where much of his family is from, and he calls himself a Nicaraguan. But as his travels took him throughout the world, Chepe sometimes found himself struggling with who he was. Was he American while he lived and worked in the United States? Was he Colombian when he lived in Colombia? Always a foreigner, Chepe found he had a unique view of the world around him, and also of his sense of self. It was this feeling of constantly being on the outside and his love of the subject of identity that drew Chepe to portraits—but why from the back?

“When I started observing people from the back, I came to realize all of those features you find in the face, you can find in the back,” Chepe said. “Everyone is aware of everybody else’s back, but not very many people are aware of our own backs. It is the personality like the wrinkles in the pants and the shirt, how things fall and move, that tell you so many things about the person.”

Chepe’s quest to capture the details that would provide this sort of familiarity is exhaustive. The attention to color, the care in the folds of the clothing and unassumingly natural poses and movement of the subjects are the result of a keen eye and lots of research.

On a visit to Grenada this previous summer, Chepe took over 3,000 photos in just three weeks, and the entire series of paintings was completed in a similarly rapid pace of about four or five months.

Paintings were worked on sometimes two or three at a time, and Chepe varied from spending eight to 10 hours on one painting to spending two or three hours on several different paintings. While preparing for the exhibit, he would carefully flick some dust away from a canvas, or gently rub off an offending crumb. Every detail and every aspect of each painting was carefully planned, down to the colorful pushpins used to display the canvases on the wall.

“The canvas is off the stretchers, which relaxes the canvas,” Chepe explained. “Originally I was going to use magnets, but the paintings got too big, and I would need probably $80 worth of magnets for each canvas in order to hold it up. So I thought, what about pushpins, colored pushpins? To me, they related to the colorful folklore and the vibrant people of Nicaragua, who are always loud, always textured, always colorful. So I started associating all of this colorfulness with the colored pushpins.”

Using pushpins to mount the canvases also gives a cohesiveness to the images that a formally stretched canvas would have broken—all the paintings sit on the same plane, instead of separately framed spaces.

The paintings in this particular show are done in oils on canvas that had a first coat of white house paint. Chepe appreciates the long tradition and implied preeminence of oils, but he has worked with all sorts of materials over his 40-year career, including ceramics, metal, watercolors, pastels, sewing and even painting with dirt. “Soil, actually,” he said. “Natural pigments.”

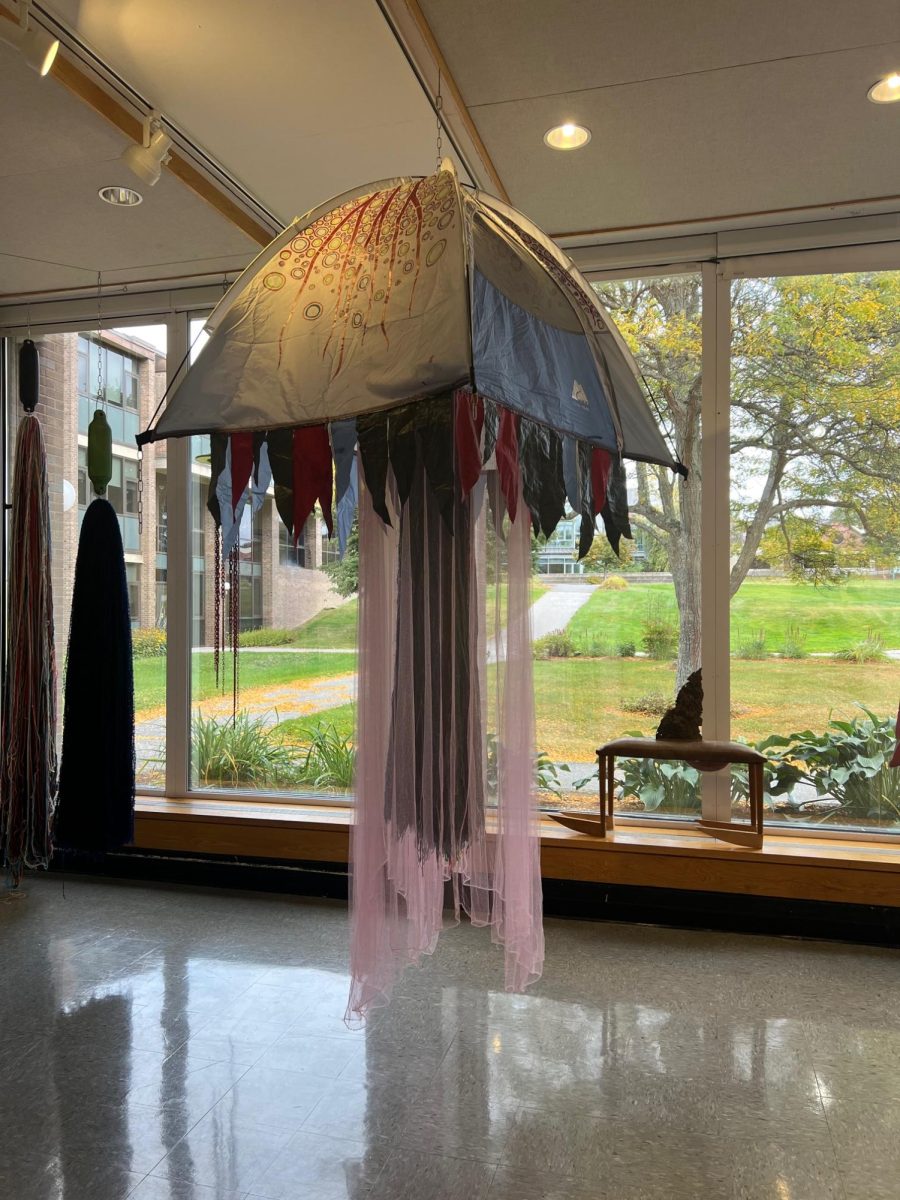

This other wide body of work is hinted at by a single sculpture centered in the gallery, observing the rest of the paintings in the show. “I still don’t know how I feel about this piece,” he said. “I don’t know if it fits in with the rest of the show.”

The sculpture in question is tall, spindly and wild, a twisting column of metal mesh, canvas, papers, documents relating to Chepe’s education at Johnson and found items, anything from salad tongs to wooden spoons, from paintbrushes to a deer spine. At the bottom are a few ceramic figures and one metal figure, all of women with physicality reminiscent of the ancient sculpture of the Venus of Willendorf.

“It is a self-portrait,” he said. “I got the sensation that the show was too flat, too silent. I needed to add noise, to add texture. There’s plenty of color and texture in the paintings, but I really needed something three-dimensional that brings this texture to the viewers when they come and look at the paintings and they see the relation between this kind of a sculpture and the paintings. This piece has yin and yang, the [male] roughness of the metal, female painting and drawing inside. The cooking elements also represent me because I am a chef. That is how I make my living, through cooking. All of the paperwork is from going to school here in Johnson for three years, handbooks, memos and bills, many bills. It shows the happy times, the anguish, that it took to accomplish this.”

“Retratos de Espaldas” is in the Julian Scott Memorial Gallery, located inside the Dibden Center of the Arts, until Feb. 11.