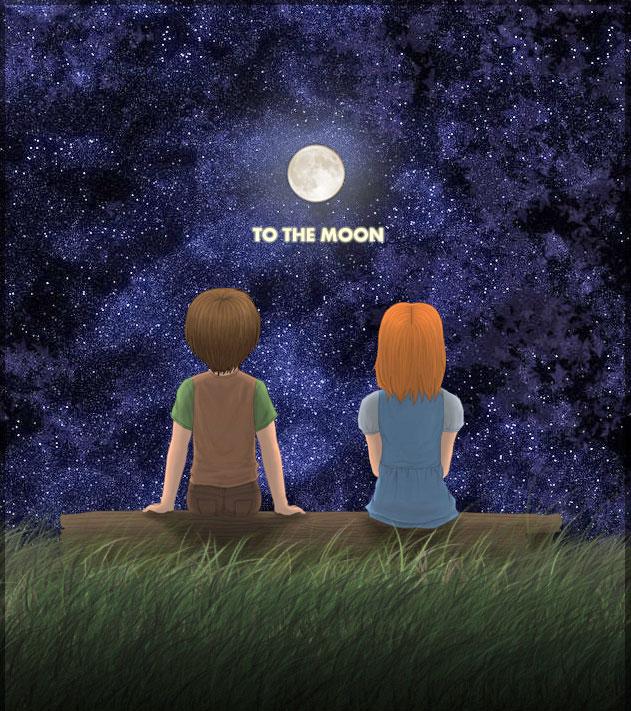

“To the Moon”: indie game with big heart

What is the first thing that comes to mind when someone says the words “video game”? Probably a popular game like “Call of Duty” or maybe a controversial one like “Grand Theft Auto”? The last game that most people would think of is a small indie game called “To the Moon.”

“To the Moon” is a short 4-to-5 hour-long game that came out for the PC in 2011. The game sports 16 bit, 2-D graphics and was made almost entirely by one developer, Kan Reives Gao. It is set in the modern day, albeit with some technological advances.

As far as gameplay goes, the player controls the characters with the arrow keys to prompt them to walk around and interact with things in their environment. The narrative is told through dialogue between characters and these scenes are how the player experiences most of the story. The only “challenge” to the game consists of a few light puzzles every now and then that the player completes to move forward in the plot. There are no bad guys to shoot, no intergalactic wars to stop, and no princesses to save. What then could possibly make this game so memorable?

On the surface, the premise seems fairly simple: you play as two doctors who are sent to artificially fulfill the wishes of the dying (the doctors make a person think they did something they always wanted to). The person they have been sent to help in this game is an elderly man on life support named Johnny. Johnny’s wish appears to be straightforward – he wants to go to the moon.

However, this is where the narrative complexity starts to emerge. For the doctors to fulfil people’s wishes, they first must know why someone wants what they do. Using advanced technology, the doctors are able to experience a person’s memories by wearing a special helmet that links their brains together. By catalyzing a decision that was never acted upon in real life, they are able to restructure the person’s memories to make them think they fulfilled their wish.

Johnny’s case is difficult in this sense. No one in his family knows why he wants to go to the moon. This keeps the doctors from fulfilling his wish, so they must travel backwards through his memories (from present to childhood) to find out why this bizarre wish is his final desire in the short time he has left on this Earth.

The characters in the game are not extraordinary at first glance. They consist of Johnny, his recently deceased wife named River, his caretaker and her two children, and the two doctors you play – Eva Rosaline and Neil Watts. The dynamic that exists between Eva and Neil is complex, as part of their relationship involves disagreements about what to do during intense morally gray moments that come with their job. The other part, however, is a playful interaction where Neil speaks his mind and Eva rolls her eyes in disapproval. Though I have nothing in common with any of these people or their predicaments, I found myself incredibly invested in their lives.

Having played more video games across genres and platforms in my lifetime than I can remember, there have invariably been some emotional moments where I have felt truly sad for the small amalgamations of pixels lamenting a recent tragedy on my T.V. or computer screen. But never in all of my years have I ever cried in response to some new revelation within a game. “To the Moon” changed that.

After getting to know the loving people Johnny met, watching his entire life’s story unfold before my eyes, and finally learning why he wanted to go to the moon, it was almost impossible for me not to get emotional in response to the touching narrative the developer had so artfully crafted.

This response was due to more than just the story, however. The music in the game (also made by Gao) does a wonderful job setting the mood. When there is a quiet, reflective moment, the music is soft and mostly composed of piano. When the pace quickens and time becomes a more pressing factor, the music shifts into notes from a synthesizer, indicating danger. During happier moments, the music is lively and full of bright chips and chirps.

Lastly, the song “Everything’s Alright,” sung by Laura Shigihara (Plants vs. Zombies, Melolune), is one of the few pieces of music with words in the game, giving it more emotional weight.

Though the graphics are modest, the characters are expressive, due not only to the phenomenal writing during deep, thoughtful sequences, but also to the wacky expressions Neil becomes known for, such as, “Holy overcooked macaroni, the kid’s in the theater all by himself! What a loser!” These exclamations sprinkled in throughout the narrative keep the story from ever becoming too heavy. Locations, too, are detailed, with small touches such as a teapot or soccer ball making each area feel unique and lived in.

As far as awards go, “To the Moon” won “Best Story” and was nominated for “Best Music,” “Most Memorable Moment,” “Best Writing/Dialogue,” “Best Ending,” and “Song of the Year” in GameSpot’s Game of the Year awards. The game has a score of 81 on review aggregate site Metacritic, indicating “generally favorable reviews” by 26 critics. On Steam, an online digital games distribution platform, the game has “Overwhelmingly Positive” reviews, which means that based on 20,600 reviews, 97% of them are positive.

“To the Moon” is available to download on Steam for $9.99 and the soundtrack is available to download for $4.99.

There have since been two free minisodes and a comic released, with an ancillary game, “A Bird Story,” released as well. This features another patient of Eva and Neil.

The next game in the main series is called “Finding Paradise” and does not yet have a release date.