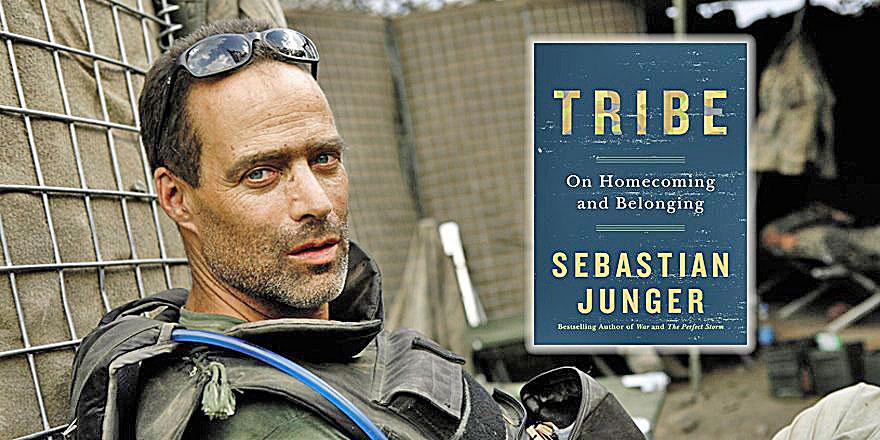

“Tribe: On Homecoming and Belonging”

Are you looking for a book that deals with issues you normally wouldn’t think about? How about heart-wrenching personal tales? If so, then “Tribe: On Homecoming and Belonging” by Sebastian Junger is the novel for you.

The latest offering from Junger, published in May of 2016, “Tribe” addresses what happens to veterans and their minds and lives upon returning from war. A published author since 1997, Junger’s body of previous works includes such titles as “The Perfect Storm,” “Fire,” “War,” and “A Death in Belmont.”

To start with, the book is pretty small, which is nice. The page count tops out at 153 pages, which does not count the source notes. This makes it easy enough to breeze through the book rapidly.

As the name would suggest, one of the main themes of the novel is that of tribe. The first section deals with this idea by focusing on the American Indian population and the !Kung tribe, who live in the Kalahari Desert that covers much of the southern portion of Africa.

A description of the book online says that in the novel, Junger asks, “How do you make veterans feel that they are returning to a cohesive society that was worth fighting for in the first place?” And certainly, there is a section of the book dedicated to answering that question. But in terms of physical book content, it was a pretty small segment of the actual novel.

So while Junger did talk about returning veterans, it seems like he couldn’t quite stick to any one solid theme. Perhaps if the book had been larger he could have spent more time on these important aspects. Out of the four sections that make up this book, there is only one that really talks about soldiers returning home from war, which Junger says is the main theme of the book. But there just wasn’t enough time spent.

One of the things that is done really well in this book is the actual writing, the prose. It felt more sophisticated than everyday conversational tone, but remained just as easy to read. There was no need to strain myself trying to understand the meaning behind what he said.

The book fits in well with the rest of Junger’s works on war. The most notable of these is his film series: “Restrepo,” “Korengal,” and “The Last Patrol,” the last of which shows “what it means for combat soldiers to reintegrate into daily American life,” according to The Boston Globe.

“Tribe” does bring up an interesting point when Junger says that the number of veterans with PTSD is significantly lower in countries, like Israel, that have mandated military service. Since the Israelis are closer to the constant fighting, and most of the citizens have been in the military at one time or another, the population understands the problems of the soldiers better, resulting in lower amounts of PTSD.

“In Israel, where around half of the population serves in the military, reflexively thanking someone for their service makes as little sense as thanking them for paying their taxes. It doesn’t cross anyone’s mind,” says Junger.

There seem to be four main themes in this book, as broken up by the chapters, with one of the more important dealing with tribal life versus modern industrialized society, and asks if humanity was not better off in the age when everyone lived in tribes. “In hunter-gatherer terms, these senior executives are claiming a disproportionate amount of food simply because they have the power to do so,” says Junger on page 33. “A tribe like the !Kung would not permit that because it would represent a serious threat to group cohesion and survival, but that is not true for a wealthy country like the United States.”

In the end, this book is worth at least a read-through, if only to start the much-needed conversation about the treatment of veterans in this country.