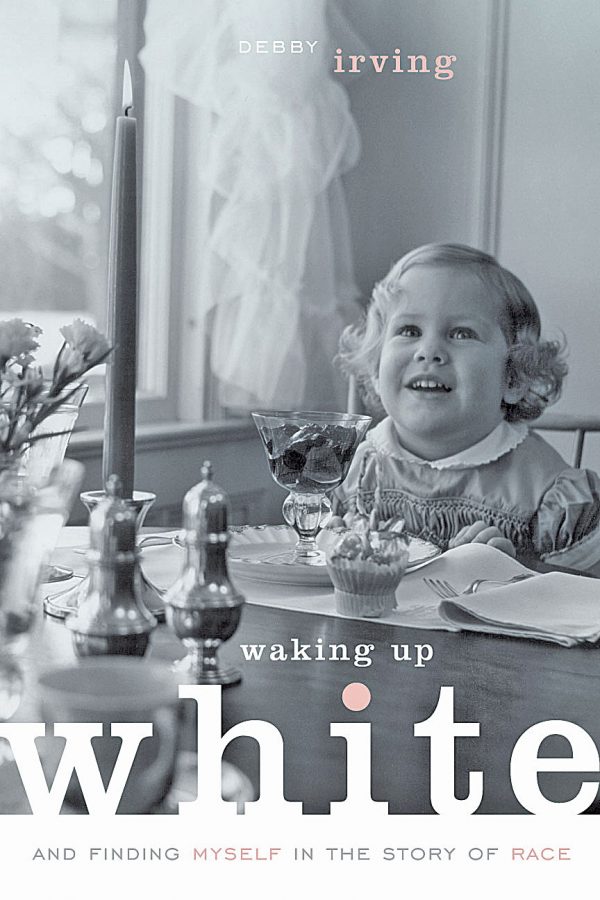

A new look at white privilege

If reading Coates’ “Between the World and Me” wakes us up to white privilege, Debby Irving’s “Waking Up White” hammers it home. Dr. Na’im Akbar, in his appearance in the film, “White Privilege 101,” defines white privilege as “a specific set of options, opportunities, and opinions that are systematically gained and maintained at the expense of people who are not white.”

Irving, born into a world of privilege as a wealthy, white, Anglo-Saxon protestant, becomes attuned to white privilege as she seeks to educate herself about it, and scrutinizes her life to recognize it. She seeks out guides and situations to discover and explore the conversations whites need to have with each other in order to move out of privilege and into equity for people of color. Irving owns up to her own racism and her guilt and shame around it, and acknowledges that for her and for most whites, to live with the intent of recognizing racism, calling it out and seeking equity in forms like restorative justice is a life-long commitment and obligation.

Besides examining her life, Irving also examines America’s history, one based on and shaped by the white male. Take, for example, the GI Bill after World War II. The U.S. Government designed this bill with the white male in mind; people of color, fighting in the same war for the same side, rarely received benefits. So the white males got educated and then got the better jobs and positions of power, earned enough to take out a streamlined mortgage to buy the better homes, and lived lives that allowed for the accumulation of wealth and continued positions of power. That was Irving’s father’s legacy to her. This legacy lives on.

Irving quotes a woman in one of her classes as Irving struggles with the concept of systemic racism: “All racial groups have problems with people in other racial groups . . . White folks have not cornered the market on that. The difference between white folks and everybody else is that they have the power to turn those feelings into policy, law, and practice. White folks run everything in this country.”

It’s not just the government though; Irving calls attention to the racism she sees in her everyday life as a mother and teacher. Because of white privilege, she doesn’t have to think about what she wears as she takes out the garbage. If she’s in sweat pants, she’s not held to representing her entire race. Her neighbor, a person of color, is held to this standard by the neighborhood and, to avoid a stereotype, dresses professionally every time he steps out of the house.

She also points out that for people of color, race is something they talk about every day because it’s part of every decision and experience they have. White people rarely talk about race because it’s not even in our consciousness to see our part in it — unless we are attuned and realize that of course it’s the big issue.

Irving provides a list of excellent references for starting conversations about racism. And throughout her book she asks us questions to help us scrutinize our lives in regard to white privilege. After reading this book, I consider myself a neophyte but moving in the right direction. I can now step back enough to see that I am indeed part of a race; I’m not just “Lisa Kent” going about in the world. What I say and what I do does matter in regard to equity for people of color. I can make positive change. Please read this book and begin your own journey.