Binta M. Colley comes to Dibden

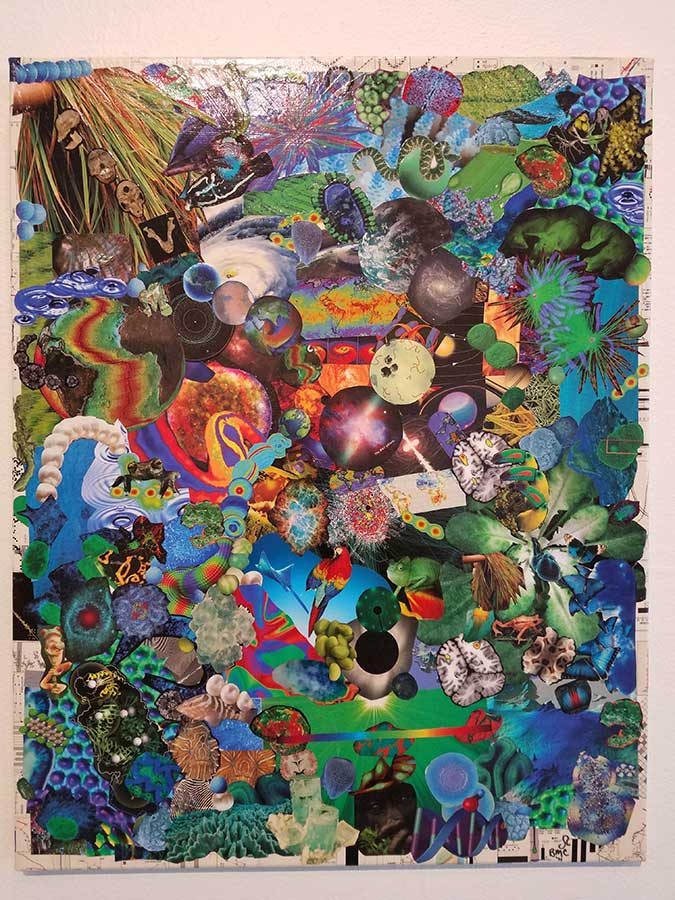

“My Brain on Botany” (2011)

If you take a walk by Dibden any time in the near future, be sure to check out the new art exhibit in the Julian Scott Memorial Gallery in Dibden Hall by Binta M. Colley entitled, “It’s All in the Details.”

It was displayed Feb. 6, and Colley gave a talk to launch its opening.

Her work was showcased as a Creative Audience event for the campus, but also welcomed community members and friends of the artist. The turnout was very good for 3 p.m. on a Wednesday, and had a lovely atmosphere.

Most of the works featured in the exhibition are detailed sketches of flowers and plants as well as a couple outliers that she did as separate projects. Among my favorites were “Pastinaca sativa – Wild Parsnip” done in 2018, and “Alstroemeria aurea” done in 2015.

Colley described her experience working on her certificate at the New York Botanical Gardens, which she will be finishing in April. She has been working in this program for seven years and has hit a couple roadblocks along the way. She had submitted three works for her final portfolio, Anthriscus sylvestris- Wild Chervil, Aegopodium podagraria- Goutweed, and Pastinaca sativa, but they got rejected for technical reasons. “Oh and they also said, ‘You’re fine in terms of your skills,’” she explained, “‘It’s just, you didn’t follow the rules.’”

“Batanseh (Wollof” (2008)

The audience laughed in reply to this comment by a committee trying to stifle Colley’s stunning artistic choices. She is going to be following the rules while she wraps this project up, saying that it is important to not give up if you want to achieve something. “Bottom line is: never give up,” she said, “And when you put that much effort into whatever you do, have enough confidence in yourself to go, ‘You know what? I can do this.’”

Colley’s talk explored the similarities between science and art. “One of the issues for me in terms of art, is the fact that art and science are sister disciplines,” she said. Colley described how Leonardo Da Vinci did fabulous works involving the human body and creating machines that should be able to fly and explaining various scientific thoughts in his works.

She went on to explain how art belongs somewhere in STEM programming. “Botanical illustration requires careful observation,” she said. “There’s a science. Microscopes and magnifying glasses are technology, that’s the ‘t’ in STEM. Understanding of plant functions, you can say that’s engineering because you look at the way a tree draws moisture from the ground and disperses it into its leaves and starts the water cycle. You can call that engineering: pumps work on that system. The skills to create illustrations which is the art, and precise ratios, math.”

She argued that instead of calling STEM, it should be called STEAM. “How would Darwin be able to share with his colleagues and the rest of the world all of the things that he saw, observed, when he was circumnavigating the Earth?” she asked. “He had an illustrator! He had an artist who drew all of those pieces so that people could understand what it was he was talking about.”

“Clematis” (2016)

Colley also used examples of cave paintings and other archeological finds that have helped us to see what people looked like thousands of years ago and what their lives were like. Archaeologists and anthropologists use art all the time to make scientific connections in how the Earth has evolved. “The two can’t be separated,” she explained.

And reflexively, science has given us different dyes and different textiles that we use in everyday life as a form of art in clothing, makeup and paints. “Without all of that chemistry, without all of that science, we wouldn’t have the availability of the media that we use,” she said.

She spoke about more people who had used art and science in the field of botany in order to make profound discoveries and propel observations.

She talked about George Washington Carver, who was a botanist and inventor, but originally went to Iowa State University and majored in art and music. As he was going through the program, one of his instructors looked at his drawings of plants and flowers and realized that they were incredibly accurate and pushed him to study botany. He was a perfect example of art in the service of science.

She also made reference to women from history that had part in these fields as well, as her tribute to women’s history month. One woman she mentioned was Mary Delany, who is written about in the book “The Paper Garden” by Molly Peacock. “Women spent most of their time in their gardens,” said Colley. “They understood and knew the flora of the area. The field of botany is built on their backs.”

At the age of 72, Mary Delany created over 1,000 paper collages of plants that she gathered from her garden that are so accurate that they are still on display. “Botanists of the time would come to her and look at her collages and be able to see, in the winter, the detail of the plants,” Colley explains.

Another woman of note was Maria Sibylla Merian. Colley recommended the book “Chrysalis” by Kim Todd to explore more of her life. At the time, no one knew where butterflies came from. From a very young age, she would watch the butterfly’s life cycle and study it in close proximity in her garden. She would take the chrysalises into her house and watch as the butterflies emerged. Her studies and artwork are so detailed that entomologists still use her discoveries today.

The talk was intriguing and more than just a technical talk about her art. She said it was important to her that she make her talk more interesting, as college students are so often finding themselves zoning out and not getting anything from lengthy, mundane lectures.

Colley’s works capture a moment in time in each image, as her botanical illustrations allow viewers to see plants and insects just as they were at the moment of their rendering.

Colley’s exhibit was on display until Feb. 21.

Sophomore, Journalism

Grew up in Salisbury, NH

Fall 2018 - Present

The closest I have come to fame so far is once, at a Weird Al concert, he went...

Senior, Journalism & Creative Writing

Grew up in Atkinson, NH

Fall 2018

Along with traditional journalism, I enjoy writing satire and fun feature...