Two for our times

Violence is as American as apple pie. The country was founded in armed revolution. Attempted extermination of native peoples followed. Slavery preceeded Jim Crow brutality. The United States reached an apex of world influence through victory in a world war and the prosecution of a cold war, the tools of which could still have civilization-ending consequences. Americans are obsessed with guns; we own more per capita than any other country in the world. These guns are not just for Hollywood heroes. A police officer recently used one to shoot a Black man in the back seven times. A vigilante used another to kill two people protesting the police shooting.

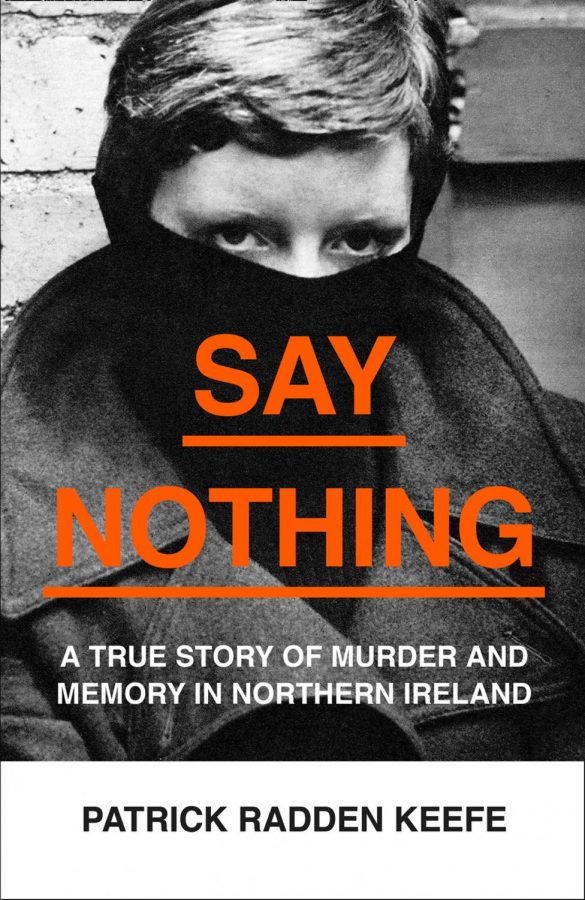

With millions of Americans taking to the streets (as reported by the New York Times), to demand racial justice, right-wing militias counter-organizing these protests, the worst pandemic in over 100 years, and the specter of a supremely chaotic presidential election, perhaps now is a good time to think about political violence – its strategic value or lack thereof and the human cost. That’s exactly what “Antifa: The Anti-Fascist Handbook,” by Mark Bray; and “Say Nothing: A True Story of Murder and Memory in Northern Ireland,” by Patrick Radden Keefe, can help us do.

“Say Nothing” is a narrative non-fiction exploration of memory, belief, sectarianism and political violence through the lens of the Irish Troubles. “Antifa” is a partisan history of anti-fascist action, providing insight gleaned from the past to further anti-fascist strategy and tactics today.

Though the contexts are different, there is a significant overlap between the two books.

Bray notes that fascism “is notoriously difficult to pin down.” But, for the book’s purposes, Bray uses historian Robert Paxton’s definition. As quoted in “Antifa,” Paxton defines fascism as: “A form of political behavior marked by obsessive preoccupation with community decline, humiliation, or victimhood and by compensatory cults of unity, energy, and purity, in which a mass-based party of committed nationalist militants, working in uneasy but effective collaboration with traditional elites, abandons democratic liberties and pursues with redemptive violence and without ethical or legal restraints goals of internal cleansing and external expansion.”

Antifa, short for anti-fascists, are loose or unassociated groups committed to fighting fascism. Though they are often left-wing – sometimes anarchist – they are not of any particular political persuasion by nature. It’s an aggressive defense posture that can draw from broad swaths of left-leaning politics. Bray writes that while anti-fascist action may entail political violence, anti-fascism rarely has revolutionary ambition of its own.

“Antifa” is a call to action, promoting resistance to fascism by any means necessary. From building “everyday anti-fascism” – creating a societal predisposition against fascist thinking and heightening the social costs for espousing fascist beliefs – to de-platforming actions and physical confrontation if necessary. As one anti-fascist quoted in “Antifa” says: “You fight them by writing letters and making phone calls so you don’t have to fight them with fists. You fight them with fists so you don’t have to fight them with knives. You fight them with knives so you don’t have to fight them with guns. You fight them with guns so you don’t have to fight them with tanks.”

Bray addresses many issues, one of which is the dual threat of machismo and fetishization of violence. “Any movement that engages with violence must remain vigilant against the tendency for the violence to overtake political goals,” he writes.

“Antifa” is both history and handbook. The history part is dry, while the handbook section is highly readable and chock-full of case studies and hands-on knowledge.

If “Antifa” is a call to action, “Say Nothing” is a warning.

If the ends justify the means, then the ends must be met, or the means become unjustifiable.

That’s what happened to Dolours Price. Price was an IRA operative who took part in bombings and disappearances during the height of the Troubles. She fought for the complete expulsion of Britain from Ireland. Unfortunately, that goal was not realized when the Good Friday agreement was signed. This left Price to sit with the ghosts of her actions. The fighting was over, but the ends had not been met. Was everything she did, in the end, unjustifiable?

Comfortable white people in the United States (I’m part of this group), often think of violence as an abomination – something against human nature. But “Say Nothing” reminds us that it is never that far away. And the killing of George Floyd showed the world that it is, in fact, a daily occurrence for far too many, even in this country. Rather than eliminating violence, we have simply shifted it to somebody else’s street corner.

Vermont’s hunting safety course teaches that you should never point a gun at something you are not willing to destroy. Seeing white gangs on the streets of Kenosha set up in sniper positions “defending” a car dealership, a question came to mind: why are you willing to kill for this? Is a person’s life worth less than a car? Do you even know what it is that you want to destroy?

“Antifa” and “Say Nothing” are particularly relevant in this vastly unstable time in our country. History tells us that there can be dire costs associated with action and inaction. These books remind us that we should look closely at both in our lives, to make sure we can live with the consequences.