Mini Maker Faire’s fairly major makings

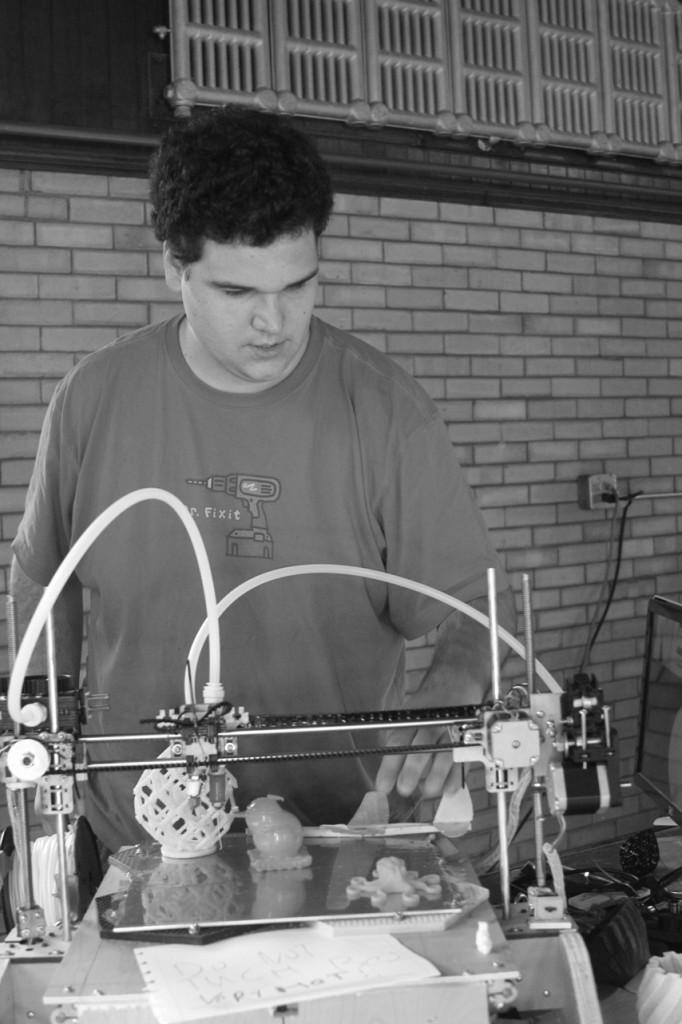

Nick Cooper looking over his 3D printer

JSC’s director of Dibden Jan Herder had a revelation late last winter as he thought about the Mini Maker Faire that Vermont would be holding in 2013: He and his technical theater students at JSC are all mini-makers with skills and products to showcase.

In love with the idea, Herder even volunteered to be program manager and in charge of entertainment and logistics at the festival, which led to a strong showing of the college’s students, alums, and faculty Sept. 28-29.

The Champlain Mini Maker Faire is an off-shoot of the Maker Faire, which was first held in on the coast of California in 2006.

The website describes the event as “part science fair, part county fair, and part something entirely new” where engineers, scientists, students, technical or science clubs, and hobbyists can share what they’ve created and learn something from others – in short, it’s a gathering for anyone who’s ever created something, thought of creating something, or likes to look at things that have been created.

But amid the remote-controlled vehicles, textiles recycled into bags and hair-ties, a robot that chased a ball like a dog, and a talking head with a moving mouth and a “consciousness,” there was another vein of creativity: art.

Against machines that can turn your virtual designs into a plastic reality in just a few hours, it seemed archaic to showcase musical instruments or dancers in the technological smorgasbord.

However, the people behind the Maker movement have no problem with dancers next to heart monitors.

On their website they continue on to say this: “… it’s not just for the novel in technical fields; Maker Faire features innovation and experimentation across the spectrum of science, engineering, art, performance and craft.”

In fact, there is now a push to change STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) into STEAM, sliding the arts between engineering and math.

Herder said this is a pivotal step for societies to embrace.

“The only way to solve today’s problems is to bring back the humanities into science,” he said. “It’s not a stretch to see artists and techs working together; there’s a fruitful interaction that working individually neither would get.”

This is the perfect place for progressive, independent tinkerers to wow the socks off their neighbors with low-budget home-made gadgets.

JSC alum Nick Cooper, a 2012 graduate with a bachelor’s of fine arts, was an inventor who brought in his 3D printer.

The printer had been a $500 6-inch cube that, using computer input, would create a real-life plastic object from the blueprints. Dissatisfied with the size limitations of the original printer, Cooper bought more material and upgraded.

The JSC graduate said he loved art and has always had an interest in technology. His works, however, often sat around his house or in his backyard as clutter. So he turned to the technological side of art and began looking into the newest technology. He said he could have bought a 3D printer similar to what he’s created with the upgrades, but what would be the fun in that?

“Also,” he said, “you can by a replicator but can’t buy replacement parts easily. With what I’ve made, if something breaks, I know how to fix it and can by the parts myself.”

Part-time Instructor of Performing Arts Dennis Báthory-Kitsz ran an outside booth working with Faire-goers to make their own ingenious instruments costing as little as $3.

While talking about the inexpensive materials he uses (floor pieces a little over $1) he threw around mathematical equations used in music as easily as he threw the bag of 10-cent screws back on the table.

“Music and math are deeply entwined,” he started with.

Báthory-Kitsz noted that spaces between piano keys are spaced to the twelfth root of two. There are 12 pitches to an octave and pitches are quantified by the cycles per second, known as hertz. Bach’s “Crab Canon” is an acoustic representation of a Möbius Strip. And, most of all, Báthory-Kitsz said that with a slight difference of hertz, Beethoven single-handedly changed the face of music forever by opening his first symphony, billed as being in C major, with a C-seventh chord instead.

Having an intimate understanding of the dance between math and music is helpful, too, when composing original works. As a musician, he said it’s his job to know acoustics and notes and how it will sound even before he hears it. There are times when a song in his head requires a frequency that a normal instrument can’t do.

“I made my own set of chimes for a certain piece,” he said. “I wanted the notes to be 10 in an octave instead of 12… I’ve made more than 40 instruments of my own.”

JSC talent also pushed what Herder called the Descartes boundary between science and art with an audience-propelled performance in an area off to the side called the Dark Stage.

Sean Clute, assistant professor of the Fine and Performing Arts, and his wife Pauline Jennings, an adjunct professor at Dibden center, co-direct Double Vision.

The couple considers Double Vision an “intermedia” company that creates experimental performances for dance, music, and video.

They said that traditional performances, such as opera, are folding fast in today’s society and they believe it’s because our world is becoming dissatisfied with just watching.

Thus, in keeping with the theme of Maker Faire, the act gave visitors the chance to make a dance. Before entering the performance space, people were given signs. On them were symbols for direction such as play, fast forward, pause, and slow motion. The visitor could choose any of the dancers to put a sign on who would then obey the written command.

To really give it a scientific kick, Jennings said Double Vision incorporated algorithms into the interactions. For instance, if Dancer #1 were given a sign that said to go to one knee, that may cause Dancer #2 to spin around in a circle. A careful observer could cipher the code to enhance the performance.

Jennings said that watching how the audience merges with the dancers is a microcosm of a culture. At first people are uncomfortable, but after a while they relax more and some even start collaborating by sequencing their signs to create a flow of dance from the performers.

Clute said he and Jennings had been at the first Maker Faire in San Francisco, where they moved from.

He said that while the style of the Faires is different, both have the same spirit.

“It is obvious the maker community has caught on,” he said, “and it is a growing part of Vermont. In fact, a huge part of the Vermont culture is maker; they do their own thing. We see it in the way they approach agriculture, build their own homes, and knit with materials from their own animals.”

Clute also said he was going to have a class in the spring called Intermedia where the concept of Double Vision would be taught to an upper-level class, introducing students to the frontier of experimental art.

He will encourage his students to take advantage of venues such as the Champlain Mini Maker Faire and showcase their visions of the dance between the humanities and technology.