A study of Buddhism and humans in India

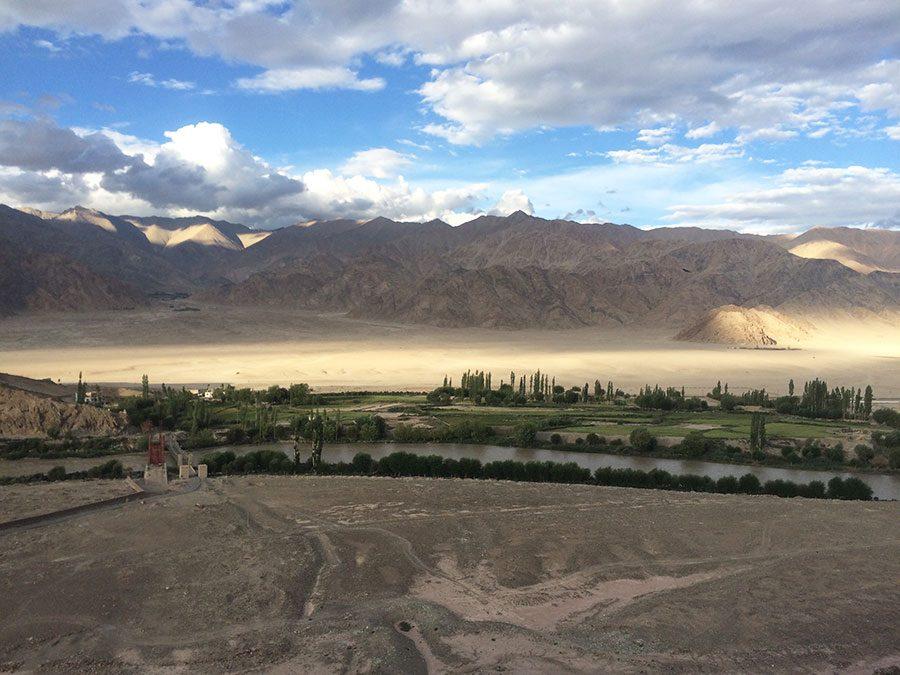

View of the Himalayas from the Dragon Hotel in Leh Ladahk, India

Twenty of us sat on a century-old wooden floor, surrounded by clay walls painted with natural pigments of red, purple and green. Around us was the faint smell of a closed-off space, perhaps the smell of your grandma’s garage.

I looked across the room for familiar smiles and glances: this was our eleventh day and I knew almost every inch of these people. I knew where they liked to eat, who their first kiss was, and even what they hated most about their parents.

I was in India, studying Buddhism with strangers from across the U.S., and today was going to be a particularly hard day. As a group, with our instructor Jim Hagan, we were going to meditate on forgiveness and then go to a local children’s orphanage in Leh, Ladahk, India. We all had a lot of forgiving to do, it seemed.

“Do you all know what compassion is?” asked Hagan in the dimly lit monastery room. There were some answers that were vague — bullshit notions of what we perceived to be love and understanding.

“Have you ever loved a girlfriend or boyfriend? You all will date someone and promise them things such as love and companionship. You will look at them like they are heaven, and that they can do no wrong,” spoke Hagan. “What if one day your boyfriend says he wants to go on vacation with another woman? Are you going to be okay with that?

“As humans,” Hagan continued, “we typically would hate that idea because we see it as betrayal. But if you have compassion, or true love for someone, you will understand and just wish them pure happiness.”

The group sat and processed this. I have had these jealous intentions. Who else is a culprit in this room?

“Today we are going to meditate on forgiveness and compassion,” said Hagan. “We are going to think of our loved ones, friends, and parents. Particularly the people with whom you do not have that great of a relationship with.

“I spent years not talkingto my father because of the way he treated my mother. Life is too short for that, and I spent years traveling. When I returned, my mother passed away six months later,” he said, voice cracking.

I could hear the heavy breathing of some in the room already. A voice you have grown to know well, breaking, will do that to you.

“Close your eyes and think of your mother’s face, or your father’s. Think of all they have done for you: the birthday parties, the Christmas gifts, covering you when you don’t have the money. They never ask you to pay them back, they just ask for love,” started Hagan.

I thought back to all the times when I have taken instead of given. I thought of the recent fight I had with them about not visiting them enough.

“Have you hurt them?” asked Hagan. “Tell them you forgive them. Have they hurt you? Picture their face and picture them asking for forgiveness.”

I could hear soft crying around me and peeked through my eyes. I saw Miguel, a 21-year-old male from Los Angeles, fighting back tears. I looked beside me and saw Joyce, whose parents are split apart by California and the Philippines, crying. To the far left was Shirin, an Iranian woman, who only knows violence and the pain from having to emigrate.

Seeing first-hand a group of young adults shamelessly and selflessly try to forgive is beyond humbling. “How do my experiences compare to theirs?” I kept imagining.

Hagan wrapped up the meditation by giving us time to just sit and breathe quietly. Of course there was a heavy air to the space as we left, but it certainly wasn’t negative. We left Rizong Gompa, or Mountain Fortress temple, and headed to the children’s orphanage.

I was immediately nervous upon arriving. Would these children be annoyed with our privileged presence? Can I connect with children halfway across the globe, or will it be awkward?

Kids came running as soon as they saw we were obviously American. Little girls wanted to show me their transcribed Justin Bieber lyrics and their ability to sing. Others complimented my tattoos and showed me where they drew on themselves, someday hoping to have one too. I was so very wrong in my previous assumptions. These Indian and Tibetan refugee children were eerily similar to me now, and how I used to be as an adolescent.

I walked over to where my roommate was standing with a young girl. “Can you write ‘compassion’ for me in my journal?” asked Celeste. We were in awe of this girl’s pristine handwriting.

Back and forth went these journal entries between Celeste and the young girl. By the time we left the orphanage, we had all exchanged contact information and vowed we would stay in touch.

Fast forward two weeks: I am back home in the United States and no longer in India. These two particular memories are my fondest, deepest, and most humble perhaps of the entire journey.

I had lower expectations than that while I had been waiting at JFK. This trip had been a lot of firsts for me, like the first time I had ever taken an Uber. Rather, the first time I had ever taken a taxi-like mode of transportation at 6:35 am in Brooklyn, New York. It was also the first time I ever set foot in a monastery, or even ate Indian cuisine.

The other day Celeste sent me a message: “I got a tattoo in the handwriting of one of the little girls from the orphanage. Her name was Dawa, which means moon. I felt so strongly connected to her.”

I related to the pain of Celeste, Dawa, and the many other individuals on the trip. Is there any better gift to bring home than that?