This article was first published in Seven Days.

From my Burlington home, I have watched in sorrow as my former neighbors, half a world away, tear each other to bits.

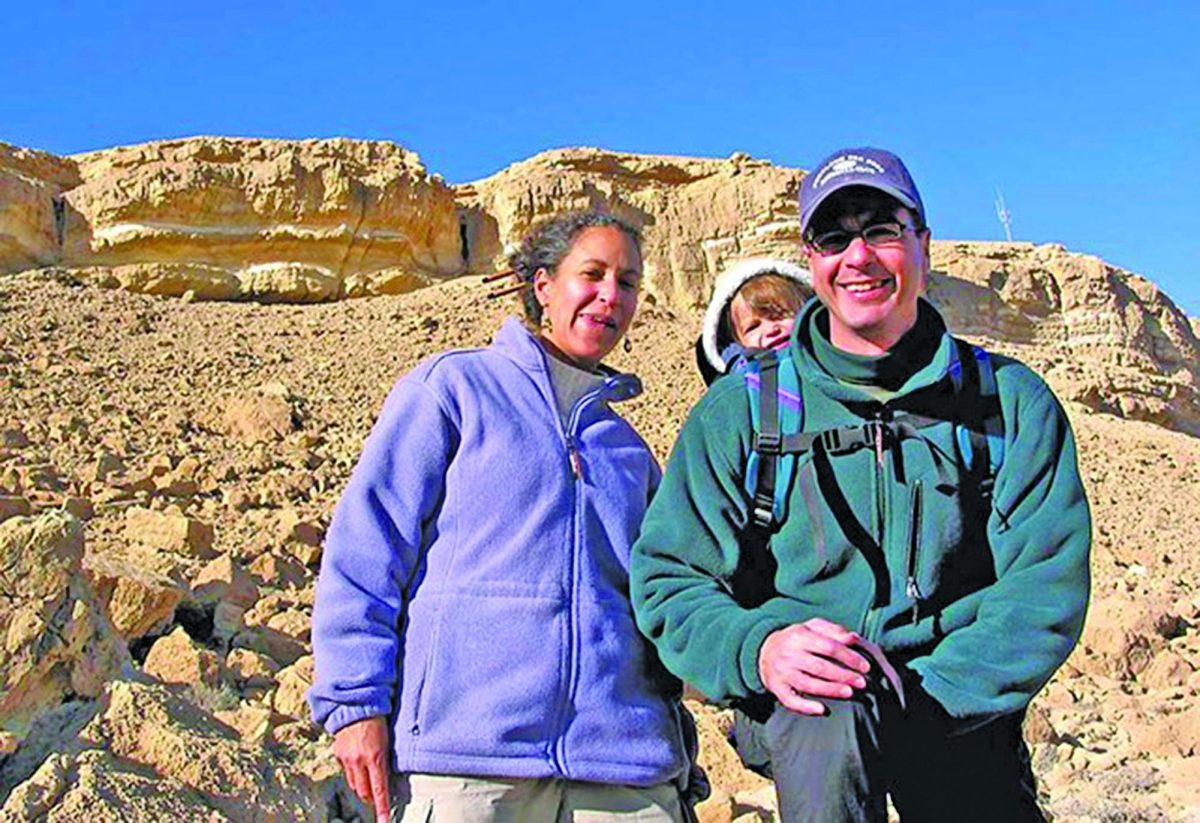

Twenty years ago this month, I moved to Jerusalem with my wife and our infant daughter so that I could cover the Middle East as a correspondent for the Los Angeles Times. It was an extraordinarily turbulent moment. Palestinian suicide bombers were blowing up crowded buses and cafés on the Israeli side, while Israel countered by assassinating suspected militants and tightening the vise on Palestinians throughout the West Bank and Gaza Strip. Each day seemed to produce fresh tit-for-tat mayhem.

But over the next four years — amid bombings and checkpoints, shooting wars in Gaza and along the border with Lebanon, and the crumbling of what we kept calling the “peace process” — our American family found a home among two peoples at war.

My work put me in contact with people on all sides of a complicated landscape: fellow journalists, politicos, shopkeepers, artists, Jewish settlers and Hamas members. I ventured to virtually every corner of Israel and all over the West Bank and Gaza. I visited the Israeli communities where on October 7 Hamas massacred more than 1,400 civilians and kidnapped 220 others. I tramped the same dense, warren-like neighborhoods of Gaza where relentless air assaults by Israel in recent weeks have killed 8,000 people, according to the Hamas-controlled health ministry. My bureau chief and I depended on our tireless Israeli news assistants and Palestinian stringers, all brave and principled souls who took many risks and, in one case, a bullet.

My wife, Monique, was no homebody. As an academic and scholar of African American history, she traveled widely, braving Israeli army checkpoints for years to teach about the Harlem Renaissance and the U.S. civil rights movement to Palestinian graduate students in the occupied West Bank. She regularly gave talks to Jewish school groups and Bedouin students on the Israeli side. Donning her mom hat, she bonded with Jews and Arabs alike through playgroups and school events and visits with her Al-Quds University students, who invited her to their villages amid the stony hills and olive groves of the West Bank.

Our daughter, Selma, crossed the divide in her own way. Although we are not Jewish, we enrolled her in a Jewish daycare and nursery school, where she learned prayer rituals and songs in Hebrew that she’d then belt out in the bathtub while I sat on a stool nearby, savoring a moment’s pause. That happy splashing often was the background track as I took calls from our Palestinian stringer in Gaza to hear about the latest Israeli missile strike or clashes between rival Palestinian factions, one of them Hamas.

Our American family found a home among two peoples at war.

We enjoyed Shabbat meals with Jewish friends and joined Palestinian friends to celebrate iftar, the nightly Muslim feast that breaks Ramadan fasting. My mind clicks through images of quotidian kindness. The Yemeni Jewish falafel maker who would place one of the freshly cooked orbs in Selma’s tiny palm every Friday before Shabbat, taking care that it was not too hot. Selma’s name never failed to delight Palestinians (and many others we met around the Arab world) for its similarity to a popular name in Arabic that comes from the word for peace. “Salma — that’s an Arabic name!” they would offer with wide-eyed glee. Jewish parents included us in their newborns’ circumcision rites and jotted recipes for dishes that we still use. A Palestinian Christian student of Monique’s put a splash pool on the terrace of her West Bank home so our girls could play together on a scorching Middle East afternoon.

Still, living amid two societies in violent conflict — even apart from the physical risk — is no easy feat. The tension can be as palpable as the scents of cardamom and sandalwood incense that thicken the air of Jerusalem’s labyrinthine Old City. It didn’t take long for journalists to learn that the conflict was often about narrative — whose humanity was violated, whose story is the truth, who gets to tell it. It’s a pressure-cooker work environment, with a tangled history to master, an unending loop of cruelties to track and every published word parsed around the world for evidence of bias. One day, we’d be munching carrot sticks and hummus with journalist friends while the kids scampered in the park and the next be racing to cover fighting in Gaza.

Neither Jewish nor Arab, I fell back on a conceit to protect against the strains: I didn’t have a dog in this fight. I was None of the Above. A young Israeli soldier once asked me at a West Bank checkpoint if I was Jewish. No, I told her, my religion is journalism. My editor said the Israeli-Palestinian story would make me a keener reporter. It did: Never was it more essential to see things for yourself. I learned to rely on verbs rather than adjectives, which could get you in trouble.

I’m not sure which adjective captures the double-barreled shock of the recent atrocities by Hamas and the deepening misery of 2 million Gaza residents without food or water amid weeks of Israeli bombardment and, now, ground war. In text messages and video calls, Israeli friends sound shattered by the enormity of October 7 and shoulder dread about the future. The Israeli kids who went to nursery school with Selma are old enough to march off to war.

My former Palestinian colleagues in Gaza face new levels of peril — two dozen journalists have been killed in recent weeks, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists. Rushdi Abualouf, the stringer whose calls used to break into my daughter’s bath-time reverie, still reports from Gaza. He recently filed a piece for the BBC describing his family’s decision to abandon their home in Gaza City for presumably safer ground in the south. He was sleeping in a tent.

Meanwhile, the discourse in the United States at times resembles the back-and-forth rocket attacks that I once covered — volleys of internet memes whose common demand is to “stand” with one side or the other, complexities be damned. Threats and hate speech have followed, along with concerns that the free exchange of viewpoints might get trampled in the process. I wait for the meme that urges everybody to take a breath and listen.

I check news updates constantly and catch myself lingering on photos of neighborhoods that look familiar, on the grief-puckered faces of Israeli parents and vacant stares of Gazan children, caked in the dust and grime of the rubble from which they were pulled. I think about the generous, entertaining, peace-minded people on both sides who welcomed, loved and protected my family and who are increasingly denied the potential of each other’s humanity with each passing year.

The sun shone bright on the winter day that the movers emptied our Jerusalem apartment for the next posting, Mexico, our cargo fattened by carpets from our travels, the baby’s crib replaced by a big-girl bed. From our window it was possible to see the looming concrete barrier that knifed around the holy city of Bethlehem. Monique and I looked across the bared white tiles of our floor, which dazzled in the sunlight. “Well,” I attempted, “that was that.” I held her and broke into sobs.

I was wrong, though — that wasn’t that. I wasn’t finished and likely never will be. If the horrors of the past month have revealed anything, it is just how thoroughly that place can wound a heart, again and again.