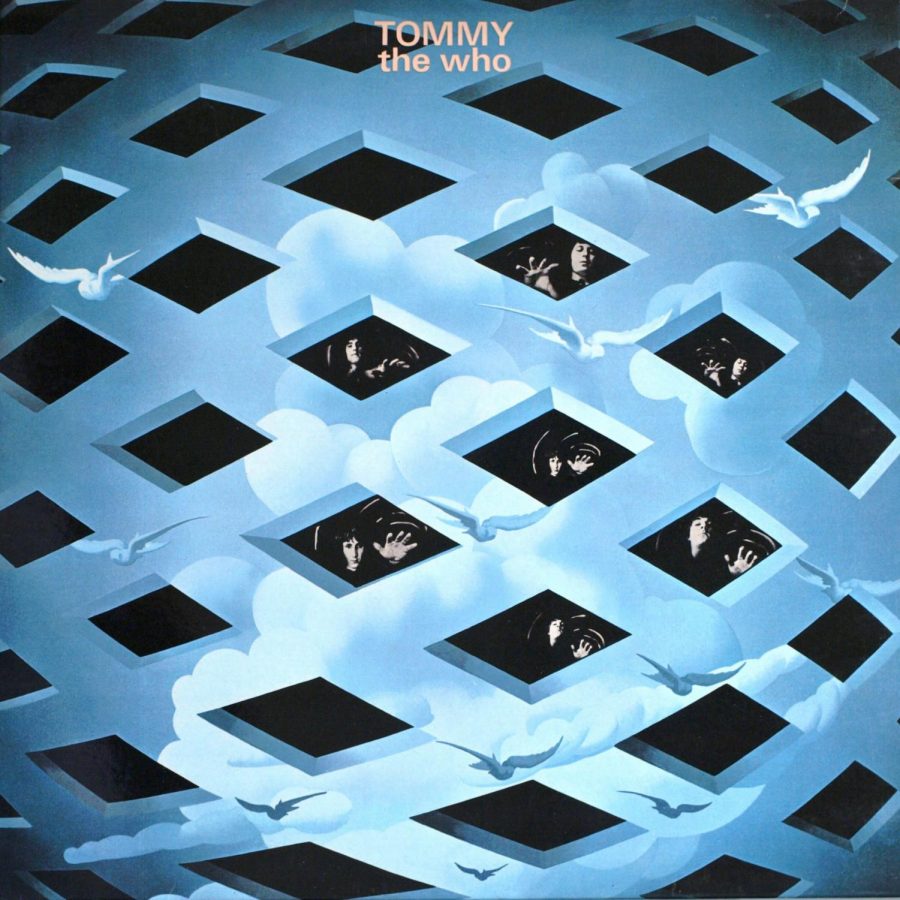

Trauma, pinball and cults: “Tommy”

Released in 1969, the Who’s fourth album, “Tommy,” was the album that coined the term rock opera. While “S.F. Sorrow” by the Pretty Things was released in 1968 and is widely regarded as the first, “Tommy” came shortly after and leaned heavily into the album-long story.

The Who were no strangers to telling extended stories with their music. Formed in 1964, the British rock band had even attempted similar projects in the past.

However, “Tommy” was the first they released successfully, and it’s widely regarded as one of the most influential rock albums of its time.

The album’s story concerns eponymous character Tommy, who goes blind and deaf as a result of childhood trauma, but eventually rises to become a cult leader. It’s a weird premise, and the Who deliver on it exceptionally well both lyrically and instrumentally.

The sounds of Tommy are weird and entrancing—be they the voices of Roger Daltrey and Pete Townshend or the wacky things the Who made their instruments do.

Townshend rocked with electric guitars and soothed with acoustics and also played keys for the album. Daltrey contributed harmonica along with his vocals, and John Entwistle commanded the bass and brass, while Keith Moon delivered on the drums.

“Tommy” features a dreamy rock-pop sound, but not without a handful of folk and jazz influences that make the Who what they are. French horns and banjo meld perfectly in “Overture,” the first track on the album.

The story part of the opera, which is what engaged me the most while I was listening, is just as strange as the sounds. It comes with a few cliche’s, such as the creepy uncle song, but overall it’s a dynamic and intriguing look at what it means to be “free” or “saved,” especially in the context of the sixties counterculture.

Another of my favorite aspects of the album is how seamlessly some of the songs play into each other. I didn’t realize one song had ended and another began multiple times throughout the album, and I was confused in all the right ways.

“Christmas” was the first song that I really jived with. At seven on the track list, it was definitely later than it could have been, but “1921” and “Eyesight to the Blind” kept me engaged long enough with their masterful harmonies, psychedelic sounds and the beginnings of a narrative structure.

My favorite track on the album has to be “Pinball Wizard,” without a doubt. It’s in my oldies playlist, and it’s one of the songs that got me to listen to the album.

The instruments blend a banjo and an electric guitar into a rock ballad that I can’t help but sing along to. On its own, “Pinball Wizard” is a high-energy, groovy tune about a kid with disabilities shredding it at the pinball table.

Within the album’s context, it’s a departure from the darker tones of “Cousin Kevin,” “Acid Queen” and “Uncle Ernie,” and foreshadows Tommy’s status as a cult leader.

Of these darker songs, “Cousin Kevin” is my favorite. Townshend and Entwistle share the vocals, and they do an excellent job portraying a violent and psychopathic kid who tortures his disabled cousin.

The instruments complement this tone, with whiny guitars and oppressive drums filling the spaces around their words, meant to menace and discomfort the listeners as much as Tommy is by the torture.

“Tommy can you Hear me?” and “Smash the Mirror” parallel each other in a few ways. Both are the same length—1:35—and both concern Tommy’s mother reacting to his disabilities.

In the first, she is compassionate and hopeful, trying to reach out to Tommy, but she turns rash and desperate in the second, growing angry with her son who has locked himself in his own mind.

“Sally Simpson” is another of my favorites, for many of the same reasons “Pinball Wizard” is. In this song, a jaunty piano and folksy guitar tell the story of Sally, a girl who convinces herself that she is in love with Tommy.

The song cements Tommy’s role as a cult leader for the album, but also tells a beautiful standalone story of a girl desperately infatuated with a public figure who will never find her to be worth his time. The harmony of the Who’s vocals give it another edge, as if it needed any.

The rest of the album after we meet and say farewell to Sally covers Tommy’s decline and the thoughts and feelings of his followers after he begins to force rules on them. Again—sixties, counterculture, you know.

“Tommy,” much like its main character, is mesmerizing and captivating. Unlike its main character, it won’t leave you with radicalized religious views or a facial scar—just a good time and a few songs stuck in your head.

Senior, Creative Writing

From Fletcher, VT

Spring 2020-Present

"Call me mommy and I'll bring you blankets and hold you while you cry."