Confessions of an ignoramus

Slater’s presentation

With a manuscript that touches on race, class, sexuality, gender, romantic inclination, criminal justice, and forgiveness, Dashka Slater, author of “The 57 Bus,” could have talked to a full Dibden about anything. I certainly expected her to talk about Sasha and Richard, and what they’d done since the book was published.

Slater made a point to mention, both in an interview and an FAQ after the presentation, that Sasha and Richard, being young people, are free to have their own lives. Though the book outlines defining moments in their existences, they are now allowed and welcomed to have lives of their own, not tied down to the book or Slater in any way.

“There’s this odd thing about writing about young people whose lives are still being formed,” she said. “My first principle is do no harm. I’m trying to have an envelope around the years in the book and then say to Sasha and Richard, ‘Go, have your lives. Have your future and not be defined forever by this book.’”

Dibden was buzzing with excitement. After Baratunde Thurston’s uproarious presentation last year about his life and Amazon appliance reviews, Slater was going to have to bring her best if she was going to wow me as much as Thurston.

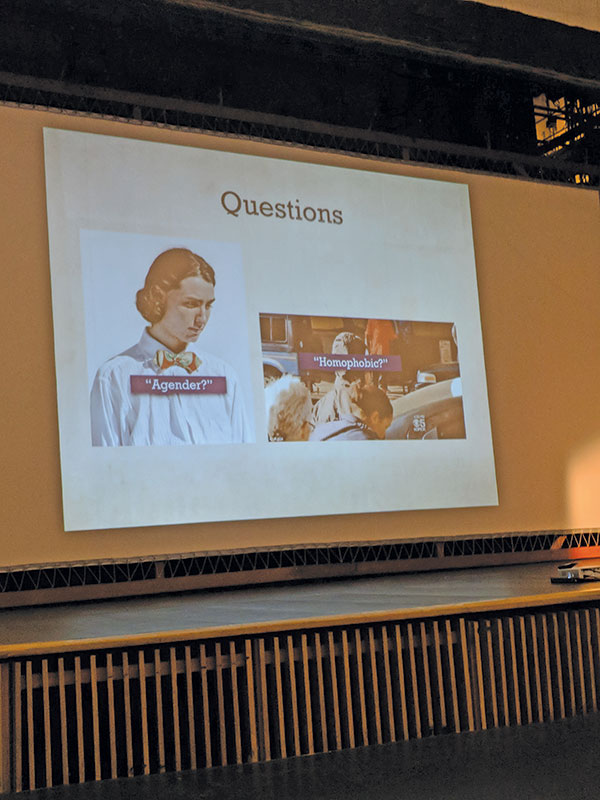

Slater’s talk, titled Confessions of an Ignoramus, was everything I wanted it to be. She is as eloquent and charismatic onstage as she is off, and her mastery of language shows.

After recounting a scenario a few months back of a fan asking her to sign an unusual object, “squash, or a gourd, I’m actually not sure of the difference,” Slater started in on her talk.

“First, I want to talk to you about ignorance,” she said. I felt a pit of annoyance in my stomach. This kind of direct talk about social justice sometimes feels forced, or like avoidance of a much bigger issue that could be talked about more specifically.

But then Slater took it in a different direction. “Not as you might expect,” she said, “about how to banish ignorance and become a worldly, knowledgeable person. No. I am here to talk about embracing ignorance, reveling in it, owning it.”

I was fascinated. Being raised, even conditioned to abhor ignorance, I have spent the better part of my life on the internet or in books, trying to learn as much as I can to stave away the inevitable conversation halter: “I don’t know about that.” If I didn’t know about a particular subject, I felt awkward and stupid asking questions.

But this, says Slater, is exactly what we should embrace. Being ignorant gives us a chance to ask questions, and learn without judgement or assumption.

Slater explained how she had come, radically, to this idea. “A radical experiment in child-directed education with mixed-age classrooms and no grades and very little adult supervision” was her third grade classroom at a so-called Free School.

“That meant I was no longer in third grade,” says Slater. “I was in Ted’s class. Math involved playing with different blocks called Cuisenaire rods. Science meant dissecting roadkill that one of the parents who was a naturalist brought in for us. The only time I can remember learning any history was when we reenacted the Battle of Hastings wearing homemade armor.”

Slater recounted a time during fourth grade when a certain homophobic slur became popular. “It felt like it appeared out of nowhere. All at once, as if by prior agreement, the boys in my class were spreading it lavishly onto every sentence like a homophobic condiment.”

Slater, 9 years old, gathered her classmates at lunchtime and explained why the word was so bad. Armed with the illicit knowledge of the 1969 bestseller, “Everything You Wanted to Know about Sex But Were Too Afraid to Ask” Slater was able to explain to her classmates in graphic detail how “according to Doctor David Rueben…two men… do it.” Afterwards, the word nearly disappeared from the class. “Even today” said Slater, “that remains one of my proudest achievements.”

This chaotic education, which continued through high school, coupled with Slater’s desire to learn as much as possible, led her to pursue an interdisciplinary major in college on Human and Environmental Relationships. “Which is how I graduated from college with a bachelor’s degree in science, having never taken an actual science class,” said Slater. “Thus earning, in spectacular fashion, the right to put B.S. after my name.”

Even after five years of schooling, Slater remarked that she hadn’t yet developed expertise in any discipline or subject. This, she said, was ignorance.

Years of crappy jobs led her to writing for a weekly newspaper. A whole new experience, Slater had to work twice as hard as her coworkers. “But my oddball and spotty education served me surprisingly well,” said Slater. “My smattering of knowledge allowed me to ask good and sometimes surprising questions. I didn’t know enough to assume anything, so I learned a great deal. So this is what ignorance has taught me. Humility and curiosity. I’ve been a journalist now for nearly thirty years.”

Slater continued her talk by explaining the way that she had researched, reported, and finally written the book. Touching once again on ignorance, she recounted the two main questions that started her journey with this story. While the questions that people sometimes ask themselves about these kind of crimes, like “Who could have done this?” and “Why did this happen?” are rhetorical, Slater said, “my job as a journalist and professional ignoramus is to ask them literally.”

These kinds of important, large questions can be hard to grapple with. Slater recounted a time when a boy sent her a letter about the story. He had re-evaluated his ideas on peer pressure, gender, and the criminal justice system. He had mentioned he was now uncertain.

“We live in a time when there is a high premium placed on certainty. When it’s seen as a sign of strength, of decisiveness, of moral purity,” said Slater. “But uncertainty is a humbler, more honest place. It is the place where curiosity is born, where investigation begins, and where understanding might be found.”

At the end of her talk, Slater encouraged the students, staff, and faculty, to revel in ignorance. “Now,” she said, “is the time to gorge yourself on the academic buffet. I hope that every time you arrive at an answer, you will seek out the exception, the contradiction, the follow-up question, and let those lead you to more questions.”

“And if you work really hard,” says Slater, “someday, you just might arrive at a vast and profound level of ignorance.”

Senior, Journalism & Creative Writing

Grew up in Atkinson, NH

Fall 2018

Along with traditional journalism, I enjoy writing satire and fun feature...