“Downstream”: a bleak picture about Vermont parental incarceration

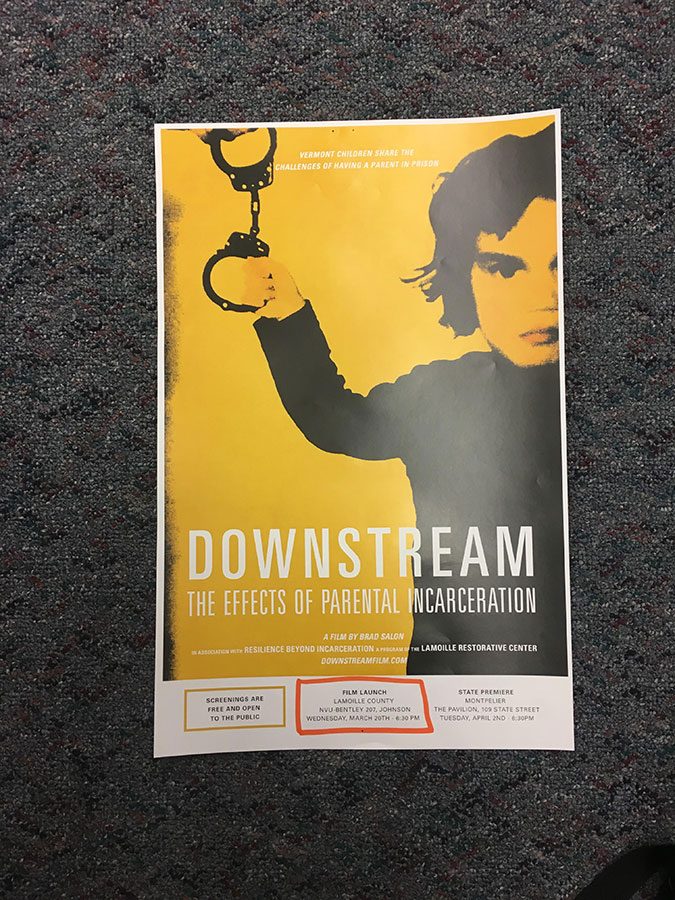

On March 20, NVU-Johnson hosted the premiere showing of “Downstream: The Effects of Parental Incarceration.” The Bearnotch production was produced by Brad Salon in association with Resilience Beyond Incarceration (RBI), a program of the Lamoille Restorative Center (LRC).

Members of the LRC were present at the screening, as well as RBI Director, Trisha Long; LRC Executive Director, Heather Hobart; Film Producer, Brad Salon and Lieutenant Governor, David Zuckerman. The film was made to support and draw attention to children whose parents have been incarcerated.

“I’m pretty sure Brad had no idea what he was getting into when he signed the contract with us,” said Hobart. “His commitment to quality and sagely patience working with us as we figured out how to capture these stories should probably earn him an Oscar.” The film, which took about nine months to produce, ran 70 minutes long.

Salon captured the full expanse of the Green Mountains with wide drone shots and close-ups into the lives of at least a dozen children living without a parent. These emotional scenes were paired with music by Canadian folk band The Fretless.

According to the film’s opening scene, one in 17 Vermont kids has lost a parent to incarceration, and 48 percent of Vermont families are living on or below the poverty line. With families already struggling to stay above water, losing a parent to incarceration can mean tipping the scale for their dependents. This also means that (if they are not adopted by a family member) the children of these parents are forced into one of three situations: entering the foster-care system, becoming homeless or becoming the breadwinner for their siblings.

The interviews conducted included both families affected by incarceration and a series of specialists from DCF, Vermont Public Schools, Center of Justice Reform, Vermont Law School, RBI, Department of Corrections, Chittenden Regional Correctional Facility and more.

While the specialists provided facts and statistics regarding the detrimental effects of parental incarceration, the families were able to share their feelings and experiences on the subject.

It also included spotlights on programs like RBI and Kids-A-Part Parenting Program. Kids-A-Part helps children whose parents are still in prison by allowing them a chance to visit them in a daycare-style setting. Babies and toddlers are able to play games and be held by their parents. Children of 13 years of age are able to sit across from their parent in the same room among other parents and kids. This allows them physical contact with their parents which would normally be denied to them.

While Kids-A-Part help children whose parents are in prison, RBI helps families tackle the effects incarceration has in the home. RBI works with families of incarcerated parents to help set goals for financial, physical, emotional and domestic stability.

Along with a clinical case manager, RBI provides a mentor for kids affected, ensuring that they have a present adult for them to play with and look up to. “Ninety-eight percent of the kids who graduate from our program avoid criminal activity,” said Long, about kids who have gone through RBI. The program also works alongside Camp Agape, a summer camp for kids with incarcerated parents. Kids are able to have fun and feel comfortable around other children affected by the same issue. The camp usually has about 30 kids attending for one week.

When the film ended, Long headed a question panel that included Krystal Whitney, one of the affected children; Lida Lutton, RBI Clinical Case Manager; Kathy Ferguson, School Counselor; Salon and herself.

Long began by thanking the families for sharing their stories and bringing this issue to light. “The kids in the family are really the heart of the film,” said Long, “and the specialists who have given a context for their stories are—as you saw—invaluable in terms of giving us insight and perspective.”

Long also thanked Salon for his work directing and producing the project, “When we first met, I asked Brad if he could agree to one condition, and that was that regardless of how far along in the process we were,” said Long, “if he’s already done the interviewing and the filming and the editing and putting the music in and having everything ready to go—if anybody in the film, any of our kids or parents decided that for whatever reason they changed their mind, he agreed that we would do what we needed to do to revamp things. I don’t know too many filmmakers who would agree to that.”

The entire panel agreed that this was one of the many things that made the movie as inclusive as possible. Salon said he “wanted everybody that was a part of the film to walk away from it with a sense of empowerment.”

When asked what people can do in their everyday lives to help these kids, the panel encouraged viewers to mentor kids at their local public schools and talk to them about their home life. The panel also suggested changing the way that we talk about incarceration in hopes of breaking down the stigma it has.

Lieutenant Governor Zuckerman spoke about this issue, referring “kindly” to a viewer who has asked, “What do us normal people do about this?”

Zuckerman said, “I think it’s really important to remember that every single one of these kids is normal. They’re kids just like any other child, and so the use of our language as we even approach these questions is part of the everyday effort we can make to change the conversation. Because when kids don’t feel normal and we continue to make them feel not normal, that continues to add more of a burden to their shoulders.”

After Zuckerman’s comment, Long mentioned the showing of “Downstream” that Zuckerman will be hosting in White River. She also encouraged viewers to spread the word about the film and to visit the “Downstream” website for more information on the subject, as well as ways to donate to RBI or Camp Agape.

At the end of the panel, Whitney made this observation: “We’re very black and white in our thinking, and sometimes it’s hard to understand that even in the way you speak to someone—even your tone—they know that you’re speaking down to them. We don’t want you to feel sorry for us. We just want you to understand that we’re already starting lower than you, and you know that we’re starting lower than you, and to understand that we’re not lower—we’re the same. Everybody’s equal, and just because I’ve been through different things than other people in my classes doesn’t mean I’m any less of a person, and that’s the most important lesson.”

Future showings are planned for Burlington, Montpelier, Essex, White River and Stowe.

Hobart says that in the following months, supporters of the film will try to branch out and show the movie at other locations as well.