Welcome back, you’re fired! Work-study positions slashed

Adriana Eldred and Rebecca Flieder

Going, going, gone

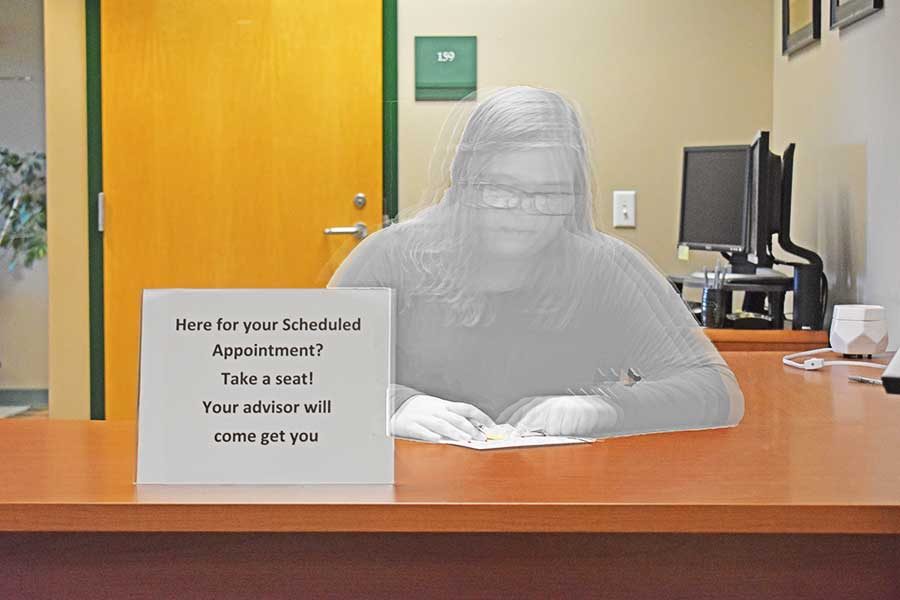

In the Advising office in Dewey Hall, a desk sits empty. The chair is pushed in, the computer powered off. No personal items lie on the desk’s surface- no pictures, no paperwork scattered, no sign of use.

And yet, the office remains busy – students amble in and out of the entrance, various office doors are closed or opened constantly, and the hum of chatter can be heard throughout the office space.

The empty desk in the entrance of the Advising office used to be the work-study station. An important role that was once the core of activity for the entire office, but one that is now no more. And the reason, according to Sara Kinerson, director of advising and registration, is not because students weren’t looking for a position.

“This past year, the university decided to approach budgeting from a different angle,” says Kinerson. A committee was formed last spring, consisting of different faculty and staff of various departments from both the Johnson and Lyndon campus, where current budgets from all departments were reviewed, cut, and proposed back to the departments. People involved included Kathy Armstrong, Jeff Bickford, Alan Giese, Chris Gilmore, Penny Howrigan, Brian Michaud, Ben Mirkin, Emily Neilsen, Lauren Philie, Monique Prive, Mike Stevens and Nedah Warstler.

“The committee was tasked with only spending so much money, and so they had to make decisions about how to meet that task and still meet those people’s needs as best they could,” says Kinerson.

The committee reviewed proposals, reviewing supply lines, travel lines, food lines, and particularly, student employment.

“What I put forth as a proposal was absolutely not what I got,” Kinerson said, noting old system of budgeting involved carrying forward what was used the previous year, while the new system involves scrutinizing what was spent and what could be dropped from the budget.

“I was very surprised when I received my budget,” says Kinerson; all direct hires, or non-work-study, had been erased, and the work-study budget had been decreased by around 87 percent.

“Our department relied heavily on student employees to run our front end,” says Kinerson, “so we had a work-study budget somewhere in the range of six or seven thousand dollars, which allowed us to have pretty much full-time coverage during the academic year.”

This would mean around four or five students would be employed in the advising office at any given time. The direct hiring budget had also been vital to the department as a full-time position would be filled during the summer, preforming important and essential tasks to the department like registering the entire incoming class, schedule building, appointment scheduling, and more. That position will now no longer be available next summer.

“Unless something magically changes, which I’m not anticipating, we will not have that position for next summer,” Kinerson said.

Advising is not the only department that has been hit with a blow to work-study funding. Nearly every department on the Johnson campus had a decrease or loss in student employment budgeting. The Visual Arts Center (VAC) cannot keep open studio hours available for as long as they have in previous years, meaning entire classes may have to be rearranged to accommodate the need for studio monitors. According to a former student employee, the Willey Library’s 15 work-study positions have been cut in half.

Academic Support Services has found itself in need of more institutional support than what it is receiving. After losing a vital grant last budgeting year, Academic Support may be unable to employ the necessary academic coaches it usually can and may have to turn away students who are not on its TRiO grant – as in, student who are not TRiO eligible, may be denied the academic services they need.

“We have no work-study,” says Karen Madden, director of Student Academic Support Services. And while they do have non-work-study money, none of it is funded through the college. In previous years, the department was afforded about $3,000, hiring around two or three students. “Now, all of the office help is being paid by TRiO.” This means the focus of the position can only revolve around TRiO students. TRiO serves about 235 students on its grant.

“We basically serve every other student in the college that wants support,” says Madden. During the last semester, there were over 500 visits for tutoring services, both TRiO and non-TRiO alike.

Academic Support recently lost a $10,000 grant from VSAC, which funded the evening drop-in tutoring hours. On top of that, the department’s tutoring budget was severely cut by the college as well, having previously funded tutoring services by half. The college now contributes to Academic Support’s budget by 44 percent. The budget went from about $50,000 a year, to $35,000 – a 30 percent cut.

“My concern is that we are going to run out of college money,” says Madden. Without enough funding from the college, many students may not be able to receive tutoring. “I can’t tutor non-TRiO students with TRiO money, so the institution will have to make a decision about what they want to do.” Madden is waiting to see how spending goes for now, and if she needs to bring it up to the provost later this year.

Toby Stewart is the controller at NVU – meaning he plays a big role in the college’s budgeting.

“Unlike previous years when budgets may just be rolled forward from year to year, the task was to take a fresh look at the budget,” says Stewart. He explains that the budget review committee met from early March to late May, meeting several times a week for hours at a time to reach their budgeting goal: cut non-work-study money, and reallocate work-study money.

“We were able to work collaboratively,” says Stewart, to allow participants from both campuses to work together using technology like Zoom. He explains that the goal was to keep the existing budget for work-study, but to redistribute it between both campuses, and to cut the non-work-study budget.

“The direct hire levels have come down,” he says. “So that kind of started the domino effect of how then we reallocate.” Student employment is funded through two pools of money: work-study, and non-work-study, or direct hires. As a result of the non-work-study budget being reduced, work-study money supplemented necessary positions. Budget revisions were approved by the executive team, consisting of President Elaine Collins, Provost Nolan Atkins, Dean of Administration Sharron Scott and Dean of Student Affairs Jonathan Davis.

So, the committee was left with the impossible decision to take from one department and give to another. It seemed, however, that Lyndon’s campus had the most shifts. Lyndon relied more on direct hires then Johnson, and so with the money gone, had to turn to work-study.

When asked if Lyndon received more work-study money than Johnson, Stewart responded, “There was no conscious decision to move “x” amount of funds from this campus to that campus. It was evaluated based on department by department… But, yeah, there are cases where departments at Lyndon would receive more than they had last year, and you’ll probably also find those departments that are going to be receiving less at Lyndon.”

Despite the decrease in student employment funding, there have been no changes to work-study eligibility to students, meaning, while students qualify for work-study, there may be more students than positions.

“We’ve never guaranteed employment here or at Lyndon,” says Stewart. When asked if he thought students may have a more challenging time finding work on campus, he pointed out the fact there were other departments like the Physical Plant and Maintenance that often don’t have enough work-study positions filled.

“A lot of it comes down to a match up of what the student is looking for and what they’re able to do,” says Stewart. “For example, I know in the past that there always seems to be a big need for areas like Physical Plant and Conference and Events Services, and not everyone is going to choose to pursue those jobs.”

Bethany Davis, senior in the art department, has been on the receiving end of this change. “I worked for the Dibden office last semester and was hoping to work again this semester,” Davis says. “I owe 1,000 dollars on my fall bill. I feel like crap not being able to work again.” She, like many students, is struggling to cover the cost of outstanding school payments, as well as pay for necessities such as car payments, school supplies, and food. “Not being able to have this job is kind of screwing me over and I feel useless and helpless for myself…I’m in a tight financial aid situation and trying to fix it has been hard,” she says.

Whatever explanation – or justification – may be handed to students, it will not change the fact that across the Johnson campus, in advising, admissions, and the Visual Arts Center, there are empty desks that once played an important role in students’ lives: knowledge of security, however small, that made the difference to students in need.

Senior, Journalism & Studio Art

Grew up in Craftsbury, VT

Spring 2018 - Present

I got a black eye and mild concussion in Las Vegas during a rugby...